They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another's throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don't have any kids yourself.

Er hatte keine Kinder, der englische Dichter Philip Larkin, da hat er sich schon an sein Gedicht This Be The Verse gehalten. Es ist ein Gedichtanfang, der im Gedächtnis bleibt wie ein guter Klospruch. Im letzten Jahr hat ein hoher englischer Richter die erste Strophe bei der Verkündung des Spruches in einem Sorgerechtsfall zitiert. Wenn viele Engländer nichts von Philip Larkin kennen, diese Zeilen kennen sie immer. Aber was so despektierlich obszön daherkommt, gewinnt in den Zeilen Man hands on misery to man. It deepens like a coastal shelf doch eine gewisse Grösse. Larkins Lyrik ist keine Lyrik der großen Worte, sie vermeidet jede Sentimentalität, seine Sprache ist schlicht, der Ton unterkühlt. Kritiker haben ihm ein lack of emotional involvement vorgeworfen. Wohl zu Unrecht, allein das kleine ➱Gedicht über den Rasenmäher und den Tod des Igels spricht dagegen.

Seine eigene Kindheit hat er als dull, pot-bound and slightly mad beschrieben. Er trägt aber ein schweres Erbe mit sich herum, über das er nie gesprochen hat. Sein Vater, der der Kämmerer der Stadt Coventry war, war ein begeisterter Nazi. Hatte die Reichsparteitage in Nürnberg besucht. Musste 1939 von seinen Vorgesetzten gezwungen werden, das Hitlerbild in seinem Dienstzimmer abzuhängen. War stolz darauf, dass er tausend Särge aus Pappe ein Jahr vor der Bombardierung Coventrys bestellt hatte. They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

Planted deeper than roots,

This chiselled, flung-up faith

Runs and leaps against the sky,

A prayer killed into stone

Among the always-dying trees.

Windows throw back the sun

And hands are folded in their work at peace,

Through where they lie

The dead are shapeless in the shapeless earth.

Because, though taller the elms,

It forever rejects the soil,

Because its suspended bells

Beat when the birds are dumb,

And men are buried, and leaves burnt

Every indifferent autumn

I have looked on that proud front

And hands are folded in their work at peace,

Through where they lie

The dead are shapeless in the shapeless earth.

Because, though taller the elms,

It forever rejects the soil,

Because its suspended bells

Beat when the birds are dumb,

And men are buried, and leaves burnt

Every indifferent autumn

I have looked on that proud front

And the calm locked into walls,

I have worshipped that whispering shell.

Yet the wound, O see the wound

This petrified heart has taken,

Because, created deathless,

Nothing but death remained

To scatter magnificence.

And now what scaffolded mind

And now what scaffolded mind

Can rebuild experience

As coral is set budding under seas

Though none, O none sees what patterns it is making?

Während Daddy noch über seinen Coup mit den Pappsärgen triumphiert, schreibt sein Sohn nach der Bombardierung von Coventry dies Gedicht, A Stone Church Damaged by a Bomb, es ist eins seiner ersten Gedichte. Zehn Jahre später in dem Gedicht I Remember, I Remember ist Coventry für ihn schon weit weg.

Coming up England by a different line

For once, early in the cold new year,

We stopped, and, watching men with number plates

Sprint down the platform to familiar gates,

'Why, Coventry!' I exclaimed. 'I was born here.'

I leant far out, and squinnied for a sign

That this was still the town that had been 'mine'

So long, but found I wasn't even clear

Which side was which. From where those cycle-crates

Were standing, had we annually departed

For all those family hols? . . . A whistle went:

Things moved. I sat back, staring at my boots.

'Was that,' my friend smiled, 'where you "have your roots"?'

No, only where my childhood was unspent,

I wanted to retort, just where I started:

By now I've got the whole place clearly charted.

Our garden, first: where I did not invent

Blinding theologies of flowers and fruits,

And wasn't spoken to by an old hat.

And here we have that splendid family

I never ran to when I got depressed,

The boys all biceps and the girls all chest,

Their comic Ford, their farm where I could be

'Really myself'. I'll show you, come to that,

The bracken where I never trembling sat,

Determined to go through with it; where she

Lay back, and 'all became a burning mist'.

And, in those offices, my doggerel

Was not set up in blunt ten-point, nor read

By a distinguished cousin of the mayor,

Who didn't call and tell my father There

Before us, had we the gift to see ahead -

'You look as though you wished the place in Hell,'

My friend said, 'judging from your face.' 'Oh well,

I suppose it's not the place's fault,' I said.

'Nothing, like something, happens anywhere.'

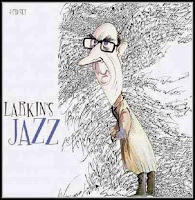

Heute vor 25 Jahren ist er gestorben. Er war einer der berühmtesten Dichter Englands. Eine Handvoll schmaler Gedichtbände, 200 Seiten Gedichte in den Collected Poems (die frühen unveröffentlichten Gedichte nicht mitgezählt), und dennoch der große Ruhm. Den Posten des poet laureate hat er nach Betjemans Tod abgelehnt, den Companion of Honour Orden hat er angenommen. Er liebte Jazz und hat jahrelang Jazzkritiken für den Daily Telegraph geschrieben. Zur Feier des 25. Todestages hat es 2010 einen Viererpack CDs seiner Lieblingsjazzstücke gegeben (Larkin's Jazz, beim englischen Amazon erhältlich). Und in Hull, wo er die Universitätsbibliothek geleitet hat, fahren Busse herum, auf denen Gedichte von ihm stehen (es gibt auch einen Bus, der Philip Larkin heißt).

Ich weiß nicht, ob man sich Larkin's Jazz kaufen soll. Was da drauf ist, ist ziemlich konventionell. ➱Zickenjazz, Trad, viel Louis Armstrong. Kein Charlie Parker, John Coltrane (the master of the thinly disagreeable [who] sounds as if he is playing for an audience of cobras) oder Miles Davis. Alles was aus Storyville kam, mochte er. Er hat sogar ein Gedicht für Sidney Bechet geschrieben:

That note you hold, narrowing and rising, shakes

Like New Orleans reflected on the water,

And in all ears appropriate falsehood wakes,

Während Daddy noch über seinen Coup mit den Pappsärgen triumphiert, schreibt sein Sohn nach der Bombardierung von Coventry dies Gedicht, A Stone Church Damaged by a Bomb, es ist eins seiner ersten Gedichte. Zehn Jahre später in dem Gedicht I Remember, I Remember ist Coventry für ihn schon weit weg.

Coming up England by a different line

For once, early in the cold new year,

We stopped, and, watching men with number plates

Sprint down the platform to familiar gates,

'Why, Coventry!' I exclaimed. 'I was born here.'

I leant far out, and squinnied for a sign

That this was still the town that had been 'mine'

So long, but found I wasn't even clear

Which side was which. From where those cycle-crates

Were standing, had we annually departed

For all those family hols? . . . A whistle went:

Things moved. I sat back, staring at my boots.

'Was that,' my friend smiled, 'where you "have your roots"?'

No, only where my childhood was unspent,

I wanted to retort, just where I started:

By now I've got the whole place clearly charted.

Our garden, first: where I did not invent

Blinding theologies of flowers and fruits,

And wasn't spoken to by an old hat.

And here we have that splendid family

I never ran to when I got depressed,

The boys all biceps and the girls all chest,

Their comic Ford, their farm where I could be

'Really myself'. I'll show you, come to that,

The bracken where I never trembling sat,

Determined to go through with it; where she

Lay back, and 'all became a burning mist'.

And, in those offices, my doggerel

Was not set up in blunt ten-point, nor read

By a distinguished cousin of the mayor,

Who didn't call and tell my father There

Before us, had we the gift to see ahead -

'You look as though you wished the place in Hell,'

My friend said, 'judging from your face.' 'Oh well,

I suppose it's not the place's fault,' I said.

'Nothing, like something, happens anywhere.'

Heute vor 25 Jahren ist er gestorben. Er war einer der berühmtesten Dichter Englands. Eine Handvoll schmaler Gedichtbände, 200 Seiten Gedichte in den Collected Poems (die frühen unveröffentlichten Gedichte nicht mitgezählt), und dennoch der große Ruhm. Den Posten des poet laureate hat er nach Betjemans Tod abgelehnt, den Companion of Honour Orden hat er angenommen. Er liebte Jazz und hat jahrelang Jazzkritiken für den Daily Telegraph geschrieben. Zur Feier des 25. Todestages hat es 2010 einen Viererpack CDs seiner Lieblingsjazzstücke gegeben (Larkin's Jazz, beim englischen Amazon erhältlich). Und in Hull, wo er die Universitätsbibliothek geleitet hat, fahren Busse herum, auf denen Gedichte von ihm stehen (es gibt auch einen Bus, der Philip Larkin heißt).

Ich weiß nicht, ob man sich Larkin's Jazz kaufen soll. Was da drauf ist, ist ziemlich konventionell. ➱Zickenjazz, Trad, viel Louis Armstrong. Kein Charlie Parker, John Coltrane (the master of the thinly disagreeable [who] sounds as if he is playing for an audience of cobras) oder Miles Davis. Alles was aus Storyville kam, mochte er. Er hat sogar ein Gedicht für Sidney Bechet geschrieben:

That note you hold, narrowing and rising, shakes

Like New Orleans reflected on the water,

And in all ears appropriate falsehood wakes,

Building for some a legendary Quarter

Of balconies, flower-baskets and quadrilles,

Everyone making love and going shares--

Of balconies, flower-baskets and quadrilles,

Everyone making love and going shares--

Oh, play that thing! Mute glorious Storyvilles

Others may license, grouping around their chairs

Sporting-house girls like circus tigers (priced

Far above rubies) to pretend their fads,

While scholars manqués nod around unnoticed

Wrapped up in personnels like old plaids.

Wrapped up in personnels like old plaids.

On me your voice falls as they say love should,

Like an enormous yes. My Crescent City

Is where your speech alone is understood,

And greeted as the natural noise of good,

Scattering long-haired grief and scored pity.

Es ist nicht so, dass er Charlie Parker et.al. nicht gekannt hätte. Aber er mag sie nicht, er verteidigt die Musik seiner Jugend in den dreißiger Jahren (Chris Barber lässt er noch gelten, weil der Trad ist). Offensichtlich das einzig Positive, an das er sich gern erinnern mag. An die Reise mit seinem Vater nach Deutschland, als er fünfzehn war, denkt er nicht so gerne.

Aber Charlie Parker und die anderen modernen Jazzmusiker stehen für ihn für mehr: I dislike such things not because they are new, but because they are irresponsible exploitations of technique in contradiction of human life as we know it. This is my essential criticism of modernism, whether perpetrated by Parker, Pound or Picasso: it helps us neither to enjoy or endure. It will divert us as long as we are prepared to be mystified or outraged, but maintains its hold only by being more mystifying and more outrageous. it has no lasting power. Hence the compulsion on every modernist to wade deeper into violence and obscenity...Holla, das klingt ein wenig nach Sedlmayrs Verlust der Mitte und Emil Staigers Attacke auf die moderne Lyrik. Für einen modernen Dichter ist Larkin erstaunlich traditionell. Er ist noch mehr als das. Wenn man seine Briefe liest (lassen Sie es lieber!), lernt man einen misogynen rechtsradikalen Fremdenhasser kennen.

Aber Charlie Parker und die anderen modernen Jazzmusiker stehen für ihn für mehr: I dislike such things not because they are new, but because they are irresponsible exploitations of technique in contradiction of human life as we know it. This is my essential criticism of modernism, whether perpetrated by Parker, Pound or Picasso: it helps us neither to enjoy or endure. It will divert us as long as we are prepared to be mystified or outraged, but maintains its hold only by being more mystifying and more outrageous. it has no lasting power. Hence the compulsion on every modernist to wade deeper into violence and obscenity...Holla, das klingt ein wenig nach Sedlmayrs Verlust der Mitte und Emil Staigers Attacke auf die moderne Lyrik. Für einen modernen Dichter ist Larkin erstaunlich traditionell. Er ist noch mehr als das. Wenn man seine Briefe liest (lassen Sie es lieber!), lernt man einen misogynen rechtsradikalen Fremdenhasser kennen.

Glücklicherweise hält er das meiste davon aus seinen Gedichten heraus. Ich hatte einmal vor Jahrzehnten einen kurzen Briefwechsel mit Larkin (allerdings nicht in den Selected Letters enthalten), da war er sehr charmant und sehr witzig. Ich mag seine Gedichte. Wenn ich sie lese, denke ich nicht an das, was ich aus seinen Briefen und aus der hervorragenden Biographie von Sir Andrew Motion über ihn weiß. ça ira. Sein bekanntestes Gedicht ist, was mich manchmal erstaunt, Church Going geworden. Für die, die es nicht kennen, setze ich es mal hier an den Schluss.

Once I am sure there's nothing going on

I step inside, letting the door thud shut.

Another church: matting, seats, and stone,

And little books; sprawlings of flowers, cut

For Sunday, brownish now; some brass and stuff

Up at the holy end; the small neat organ;

And a tense, musty, unignorable silence,

Brewed God knows how long. Hatless, I take off

My cycle-clips in awkward reverence,

Move forward, run my hand around the font.

From where I stand, the roof looks almost new-

Cleaned or restored? Someone would know: I don't.

Mounting the lectern, I peruse a few

Hectoring large-scale verses, and pronounce

'Here endeth' much more loudly than I'd meant.

The echoes snigger briefly. Back at the door

I sign the book, donate an Irish sixpence,

Reflect the place was not worth stopping for.

Yet stop I did: in fact I often do,

And always end much at a loss like this,

Wondering what to look for; wondering, too,

When churches fall completely out of use

What we shall turn them into, if we shall keep

A few cathedrals chronically on show,

Their parchment, plate, and pyx in locked cases,

And let the rest rent-free to rain and sheep.

Shall we avoid them as unlucky places?

Or, after dark, will dubious women come

To make their children touch a particular stone;

Pick simples for a cancer; or on some

Advised night see walking a dead one?

Power of some sort or other will go on

In games, in riddles, seemingly at random;

But superstition, like belief, must die,

And what remains when disbelief has gone?

Grass, weedy pavement, brambles, buttress, sky,

A shape less recognizable each week,

A purpose more obscure. I wonder who

Will be the last, the very last, to seek

This place for what it was; one of the crew

That tap and jot and know what rood-lofts were?

Some ruin-bibber, randy for antique,

Or Christmas-addict, counting on a whiff

Of gown-and-bands and organ-pipes and myrrh?

Or will he be my representative,

Bored, uninformed, knowing the ghostly silt

Dispersed, yet tending to this cross of ground

Through suburb scrub because it held unspilt

So long and equably what since is found

Only in separation - marriage, and birth,

And death, and thoughts of these - for whom was built

This special shell? For, though I've no idea

What this accoutred frowsty barn is worth,

It pleases me to stand in silence here;

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognised, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious,

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in,

If only that so many dead lie round.

Die Collected Poems, herausgegeben von Anthony Thwaite sind 1988 bei Faber und Faber erschienen (und wurden im gleichen Jahr viermal nachgedruckt). Auch von Anthony Thwaite herausgegeben (und auch bei Faber) sind die 791-seitigen Selected Letters (1992). Ein Jahr später erschien Andrew Motions Biographie Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life.

Lesen Sie auch: Philip Larkins Rasenmäher, Kingsley Amis, Michael Innes, Church Going

Lesen Sie auch: Philip Larkins Rasenmäher, Kingsley Amis, Michael Innes, Church Going

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen